Recently an interesting post came to my attention authored by the late Dr. John W. Eshlemann entitled “Junk Behaviorism”. Dr. Eshlemann criticised the phrase that reinforcement increases the probability of behavior while advocating the use of rate of response. As I had previously frequently employed the word “probability” (e.g. Introduction to radical behaviorism (Part 4 – Operant conditioning, new traits/behavior).), I was compelled to reflect on the matter.

A variation of this misconception [lack of clarity about what a reinforcer does] is that “reinforcement” “increases the probability of behavior,” or that it “increases the likelihood of behavior.” While slightly better than the even more ambiguous “increases behavior,” these still qualify as bad phrases; phrases that obscure more than they clarify. In contrast, Skinner was very clear: a reinforcer affects the RATE OF RESPONSE. More specifically, a reinforcer increases the frequency of behavior over time, where frequency refers to, and means the exact same thing as, rate of response.

To get a rate of response you have to COUNT instances of behavior and determine how many there are per unit of time. You need to determine the frequency of behavior and then see whether that frequency changes over time. If it does, and if it increases, then you begin to have some evidence that the event, or thing, functioned as a reinforcer.

In terms of probability and changes to probability, Skinner was always very clear: Probability referred to rate of response. This type of probability addresses the “how often?” question, not the “what are the odds?” question. If we loosely say that the “probability of the behavior increases,” in Skinner’s science we really mean that the response rate increased over time. The count per minute went from one level up to another level. For example, if we start “reinforcing” behavior, it’s frequency might increase from 5 per minute up to 20 per minute. Or, perhaps behavior increases from .1 responses per minute up to .5 responses per minute. If, but only if, those sorts of increases in response rate occur, do we begin to have evidence that we have reinforcement.

Dr. John W. Eshlemann (2008) – Charting versus “Junk Behaviorism” – https://jweshleman.wordpress.com/2008/11/02/charting-versus-junk-behaviorism/

Relation between probability and rate of response

Somewhat contrary to Dr. Eshlemann’s stance, the subject isn’t clear-cut. In Skinner’s works, the word probability appears regularly and often separately from rate of response. After all, not all behaviors appear in repeatable form. Determining the primacy of the two concepts in Skinner’s science was a question previously visited:

In summary, Skinner’s position on the relation between response probability and response rate seems to be that although the two are not equivalent, response probability can be inferred from response rate.

In any event, Skinner remains clear that the concept of probability plays a central role in his science of behavior: “If we are to predict behavior (and possibly to control it), we must deal with probability of response”, and “The end datum in a theory of behavior, in short, is the probability of action”.

Johnson & Morris (1987, p. 117) – When Speaking of Probability in Behavior Analysis

Reinforcement by definition affects the rate of behavior (in specific circumstances, of a specific behavior class). Can we actually gain anything by referring to probability?

Our basic datum is the rate at which such a response is emitted by a freely moving organism. This is recorded in a cumulative curve showing the number of responses plotted against time. The curve permits immediate inspection of rate and change in rate. Such a datum is closely associated with the notion of probability of action.

Ferster & Skinner (1957, p. 18) – Schedules of Reinforcement

Rate of response as the dependent variable

One must consider that a specific rate of response / frequency can actually be selected. In Science and Human Behavior (1953) this idea is presented when speaking about so-called combined schedules, albeit in an ironically unfortunate way (remember behavior is reinforced, not an organism):

We can reinforce an organism only when responses are occurring at a specified rate. If we reinforce only when, say, the four preceding responses have occurred within two seconds, we generate a very high rate.

B.F. Skinner (1953, p. 105) – Science and Human Behavior

Furthermore, in Ferster & Skinner (1957) – Schedules of Reinforcement, there is a whole chapter dedicated to the topic – Chapter 9: Differential Reinforcement of Rate. To illustrate, let’s say we want a rat to push a lever at a rate of 5 times per minute – so if a rat is too fast initially, we reinforce behavior when it slows down. While Dr. Eshlemann mentioned only the possibility of the rate of response increasing, but one would think that he wouldn’t mind us saying that the reduction of the rate of response may also indicate learning.

In this case, rather than rate of response, we may meaningfully employ probability by a careful definition of calculation – e.g. the percent of 1-minute intervals where the rat pressed the lever 5 time.

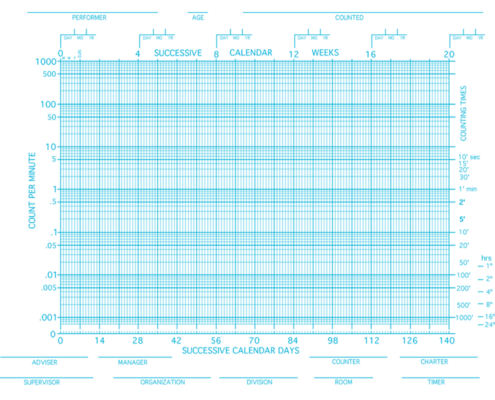

Celeration charts

I’m in no way arguing against the use of rate of response / frequency – it is by far the most pragmatic datum of behavioral science. Rate of response can be conveniently plotted in celeration charts while probability does not succumb so easily to charting. Now, knowing Dr. Eshlemann’s lifelong work with celeration charts, we might just have an idea what influenced his strongly pragmatic point of view.

The spectre of reification

Perhaps, when speaking of probability, we’re dangerously close to committing the error of reification, which is discussed in Johnson & Morris (1987). One should note a similar issue in Cognitive Psychology where behavior can be considered as a referent to some other more important processes:

A focus on behavior must not obscure the fact that even the definition and selection of a behavior unit for study requires grouping and categorizing. In personality research, the psychologist does the construing, and he includes and excludes events in the units he studies, depending on his interests and objectives. He selects a category—such as “delay of gratification,” for example—and studies its behavioral referents.

Mischel (1973, p. 268) – Toward a Cognitive Social Learning Reconceptualization of Personality

Skinner claimed that behavior is no referent but rather itself the object of science. Applying the analogy, shall we claim that the datum is the rate of response and it there is no need to consider it a referent for probability? Or maybe probability is the rare theoretical construct that is allowed in behavioral science?

Rate of responding appears to be the only datum that varies significantly and in the expected direction under conditions which are relevant to the “learning process.” We may, therefore, be tempted to accept it as our long-sought-for measure of strength of bond, excitatory potential, etc. Once in possession of an effective datum, however, we may feel little need for any theoretical construct of this sort. Progress in a scientific field usually waits upon the discovery of a satisfactory dependent variable. Until such a variable has been discovered, we resort to theory. The entities which have figured so prominently in learning theory have served mainly as substitutes for a directly observable and productive datum. They have little reason to survive when such a datum has been found.

It is no accident that rate of responding is successful as a datum, because it is particularly appropriate to the fundamental task of a science of behavior. If we are to predict behavior (and possibly to control it), we must deal with probability of response.

B. F. Skinner (1950, p. 7) – Are Theories of Learning Necessary

In closing, probability may have it’s place in behavioral science, but we should treat it carefully by not distancing ourselves from the object of study that is behavior:

The speaking of “probability” in behavior analysis is no different. In keeping it uncompromised: “There is only one rule, namely: that the descriptions should fit the events being described (Kantor, 1941, p. 48).

Johnson & Morris (1987, p. 125) – When Speaking of Probability in Behavior Analysis

Rate of responding is not a “measure” of probability but it is the only appropriate datum in a formulation in these terms.

B. F. Skinner (1950, p. 7) – Are Theories of Learning Necessary