The intersection between antiquated psychological theories about behavior and socioeconomic-historical processes is brilliantly identified and scrutinized by E. E. Sampson in his 1981 article “Cognitive Psychology as Ideology”. The article has already been cited multiple times in the blog and the relevant quote this time is:

Psychological reifications clothe existing social arrangements in terms of basic and inevitable characteristics of individual psychological functioning; this inadvertently authenticates the status quo, but now in a disguised psychological costume. What has been mediated by a sociohistorical process—the forms and contents of human consciousness and of individual psychological experience—is treated as though it were an “in-itself,” a reality independent of these very origins.

Sampson (1981, p. 738) – Cognitive Psychology as Ideology

In this post, I would like to present a prominent example of a psychologized affirmation of the contemporary social order – extended adolescence.

The statistical

For context let’s view the basic situation of the position of young adults in Europe.

Firstly, the percent of young adults that are still living with their parents:

adults-leave-the-parental-home

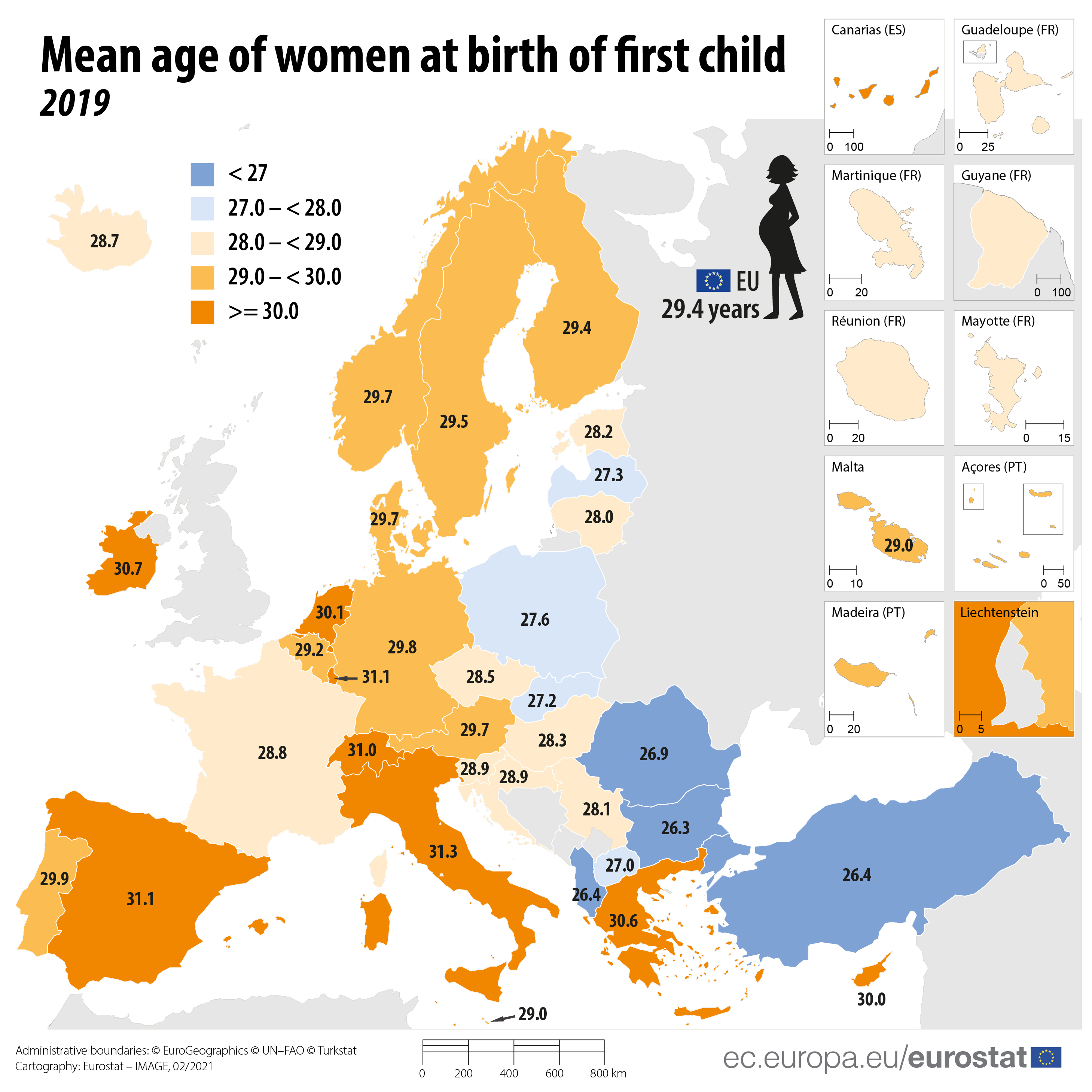

Secondly, the mean age of women at birth of first child:

If we look at historical trends for Europe or Japan, we can see that people generally move out from parental homes, marry, have children later in life and have less children overall in comparison with the 20th century. What can explain such trends?

The psychological

The idea of extended adolescence comes from a classical perspective of developmental stages in the human lifespan. Perhaps the most famous theory is Erik Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. The “stage” that interests us now is the 5th of the 8 stages – adolescence. Originally, i.e. in the 1950s, this period spanned the ages 10 to 19, but, presumably, it has experienced a modern extension with the higher end now reaching 25 or even later ages:

An analysis by researchers at San Diego State University and Bryn Mawr College reports that today’s teenagers are less likely to engage in adult activities like having sex and drinking alcohol than teens from older generations.

“Our results show that it’s probably not that today’s teens are more virtuous, or more lazy—it’s just that they’re less likely to do adult things.” She adds that in terms of adult behaviors, 18-year-olds now look like 15-year-olds of the past.

Bret Stetka (2017) – Extended Adolescence: When 25 Is the New 18

One may find also such statements, that young people now have more opportunities than before, that they want to explore the world and discover themselves, find out what they want to do with their lives and careers. Due to these expanded opportunities the youth doesn’t want to take on financial commitments or relationships. All sounds fine and dandy until we realise that we are missing any proper explanation of the behavior changes.

As with all things widely accepted in psychology, B.F. Skinner has an alternative explanation – developmental stages is no exception. The behavior of young adults does not change due to some strictly predetermined sequence – simply the social contingencies of reinforcement change after childhood:

It is no doubt valuable to create an environment in which a person acquires effective behaviour rapidly and continues to behave effectively. In constructing such an environment we may eliminate distractions and open opportunities, and these are key points in the metaphor of guidance or growth or development; but it is the contingencies we arrange, rather than the unfolding of some predetermined pattern, which are responsible for the changes observed.

B.F. Skinner (1971, p. 89) – Beyond Freedom and Dignity

The material

Even in the cited psychological and scientifically idealistic Stetka’s article, the author must grapple with socio-economic reality:

Domakonda adds that although parents can play a role in indulging extended youth, they are not the root cause. “Most are responding to their own anxieties about the new norm,” she says. “They recognize that now, in order for their children to succeed, they can’t simply get a job at the local factory, but may be faced with 10-plus years of postgraduate education and crippling student debt.”

Bret Stetka (2017) – Extended Adolescence: When 25 Is the New 18

Now, even a brief survey of current economic realities of young adults takes us further than any of developmental theories of psychology. Let’s see:

Thomas Piketty documents the increasing income and wealth inequality to the levels not seen since the late 19th century (The Belle Époque). This presents an ominous state of affairs. A way of experiencing this inequality is noting the ever rising real estate prices and wage stagnation. Furthermore, labour conditions have deteriorated – zero-hour contracts and “employees as partners” illustrate it neatly. Simply put, affordability of housing is a rising problem – the opportunities to move out are diminishing.

If a young person has the (mis)fortune to move out, it is likely he or she has to rent. The rent prices, quite expectedly, have not gone untouched and there is no wonder that related memes spring up:

Furthermore, high rent prices might mean that one needs to live with other people (cohabitate). Also, logically with rising property prices, people in cities experience space contraction – the living area is becoming smaller. We have articles such as “The newest trend in urban development? Micro units.”, and the new owners may have to live in so-called apodments that range only up to 30 square meters. Obviously, this can’t be considered a suitable environment for having children.

Even if the person owns the real estate, more often than not one has to take on debt for some 30 odd years. We must also not overlook the fact that one salary in a household is frequently not enough – now in all families, bar the most affluent of society, both members have to work. In a pyrrhic victory of financial independence, middle-class women had to join the workforce without the added financial security. One must note that lower income women always participated in labour relations, also that women always worked at home. The two-income trap that Elizabeth Warren discussed in 2004 has entrenched itself even further.

How do children fit into all of this? They require much care, time, and financial resources – with both parents working these things are often out of reach. Having children is basically a threat to one’s socioeconomic status and even a risk factor of poverty:

Our research eventually unearthed one stunning fact. The families in the worst financial trouble are not the usual suspects. They are not the very young, tempted by the freedom of their first credit cards. They are not the elderly, trapped by failing bodies and declining savings accounts. And they are not a random assortment of Americans who lack the self-control to keep their spending in check. Rather, the people who consistently rank in the worst financial trouble are united by one surprising characteristic. They are parents with children at home. Having a child is now the single best predictor that a woman will end up in financial collapse.

Elizabeth Warren & Amelia Warren Tyagi (2004, p. 17-18) – The Two-Income Trap

Do we really need a psychological theory beyond these things? Living with parents well into one’s twenties and not having children is not an “investigation” of one’s wants, is not an exploration of one’s “needs” or discovery of “oneself”. It is simply a quite mundane, dystopian reflection of the conditions people find themselves in. One might even go so far as to say that the most effective form of birth control is high and unaffordable real estate prices:

Europe is in the midst of a housing crisis. From Paris to Warsaw, Dublin to Athens, an increasing number of people in the EU are struggling to afford the rising cost of housing. Even before the start of the pandemic, one in ten Europeans were spending more than 40% of their income on housing. In urban areas in particular, many people find themselves in a dire situation and are driven out of the city. Also, the quality of housing is often deplorable. Far too many people in Europe are living in overcrowded dwellings and damp or poorly insulated homes, with unaffordable utility bills.

Kim van Sparrentak (2021) – Tackling Europe’s housing crisis

Conclusion

As the idea of extended adolescence illustrates, any political and economical circumstances may be psychologized, given a fancy name to produce credibility and to prevent further examination. When one claims that young adults “want to try something new”, “want to try different carrers”, “want to see the world”, “value experiences over material things”, one throws a veil of psychology over the socio-economic conditions that are incompatible with what a psychologist would call “independent adult life”.

We must stop seeing behavior as random, unexplainable, unorderly – humans do what they do for a reason. The psychologisation of the human condition has to be abandoned and finally interpreted through behavioral and material lenses.